Gender Roles with Text Mining and N-grams

By Julia Silge

April 15, 2017

Today is the one year anniversary of the janeaustenr package’s appearance on CRAN, its cranniversary, if you will. I think it’s time for more Jane Austen here on my blog.

I saw this paper by Matthew Jockers and Gabi Kirilloff a number of months ago and the ideas in it have been knocking around in my head ever since. The authors of that paper used text mining to examine a corpus of 19th century novels and explore how gendered pronouns (he/she/him/her) are associated with different verbs. These authors used the Stanford CoreNLP library to parse dependencies in sentences and find which verbs are connected to which pronouns; I have been thinking about how to apply a different approach to this question using tidy data principles and n-grams. Let’s see what we can do!

Jane Austen and n-grams

An n-gram is a contiguous series of words from a text; for example, a bigram is a pair of words, with . If we want to find out which verbs an author is more likely to pair with the pronoun “she” than with “he”, we can analyze bigrams. Let’s use unnest_tokens from the tidytext package to identify all the bigrams in the 6 completed, published novels of Jane Austen and transform this to a tidy dataset.

library(tidyverse)

library(tidytext)

library(janeaustenr)

austen_bigrams <- austen_books() %>%

unnest_tokens(bigram, text, token = "ngrams", n = 2)

austen_bigrams## # A tibble: 725,048 x 2

## book bigram

## <fctr> <chr>

## 1 Sense & Sensibility sense and

## 2 Sense & Sensibility and sensibility

## 3 Sense & Sensibility sensibility by

## 4 Sense & Sensibility by jane

## 5 Sense & Sensibility jane austen

## 6 Sense & Sensibility austen 1811

## 7 Sense & Sensibility 1811 chapter

## 8 Sense & Sensibility chapter 1

## 9 Sense & Sensibility 1 the

## 10 Sense & Sensibility the family

## # ... with 725,038 more rowsThat is all the bigrams from Jane Austen’s works, but we only want the ones that start with “he” or “she”. Jane Austen wrote in the third person, so this is a good example set of texts for this question. The original paper used dependency parsing of sentences and included other pronouns like “her” and “him”, but let’s just look for bigrams that start with “she” and “he”. We will get some adverbs and modifiers and such as the second word in the bigram, but mostly verbs, the main thing we are interested in.

pronouns <- c("he", "she")

bigram_counts <- austen_bigrams %>%

count(bigram, sort = TRUE) %>%

separate(bigram, c("word1", "word2"), sep = " ") %>%

filter(word1 %in% pronouns) %>%

count(word1, word2, wt = n, sort = TRUE) %>%

rename(total = nn)

bigram_counts## # A tibble: 1,571 x 3

## word1 word2 total

## <chr> <chr> <int>

## 1 she had 1472

## 2 she was 1377

## 3 he had 1023

## 4 he was 889

## 5 she could 817

## 6 he is 399

## 7 she would 383

## 8 she is 330

## 9 he could 307

## 10 he would 264

## # ... with 1,561 more rowsThere we go! These are the most common bigrams that start with “he” and “she” in Jane Austen’s works. Notice that there are more mentions of women than men here; this makes sense as Jane Austen’s novels have protagonists who are women. The most common bigrams look pretty similar between the male and female characters in Austen’s works. Let’s calculate a log odds ratio so we can find the words (hopefully mostly verbs) that exhibit the biggest differences between relative use for “she” and “he”.

word_ratios <- bigram_counts %>%

group_by(word2) %>%

filter(sum(total) > 10) %>%

ungroup() %>%

spread(word1, total, fill = 0) %>%

mutate_if(is.numeric, funs((. + 1) / sum(. + 1))) %>%

mutate(logratio = log2(she / he)) %>%

arrange(desc(logratio)) Which words have about the same likelihood of following “he” or “she” in Jane Austen’s novels?

word_ratios %>%

arrange(abs(logratio))## # A tibble: 164 x 4

## word2 he she logratio

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 always 0.001846438 0.0018956289 0.03793181

## 2 loves 0.000923219 0.0008920607 -0.04953103

## 3 too 0.000923219 0.0008920607 -0.04953103

## 4 when 0.000923219 0.0008920607 -0.04953103

## 5 acknowledged 0.001077089 0.0011150758 0.05000464

## 6 remained 0.001077089 0.0011150758 0.05000464

## 7 had 0.157562702 0.1642506690 0.05997318

## 8 paused 0.001384828 0.0014495986 0.06594619

## 9 would 0.040775504 0.0428189117 0.07054542

## 10 turned 0.003077397 0.0032337199 0.07148437

## # ... with 154 more rowsThese words, like “always” and “loves”, are about as likely to come after the word “she” as the word “he”. Now let’s look at the words that exhibit the largest differences in appearing after “she” compared to “he”.

word_ratios %>%

mutate(abslogratio = abs(logratio)) %>%

group_by(logratio < 0) %>%

top_n(15, abslogratio) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(word = reorder(word2, logratio)) %>%

ggplot(aes(word, logratio, color = logratio < 0)) +

geom_segment(aes(x = word, xend = word,

y = 0, yend = logratio),

size = 1.1, alpha = 0.6) +

geom_point(size = 3.5) +

coord_flip() +

labs(x = NULL,

y = "Relative appearance after 'she' compared to 'he'",

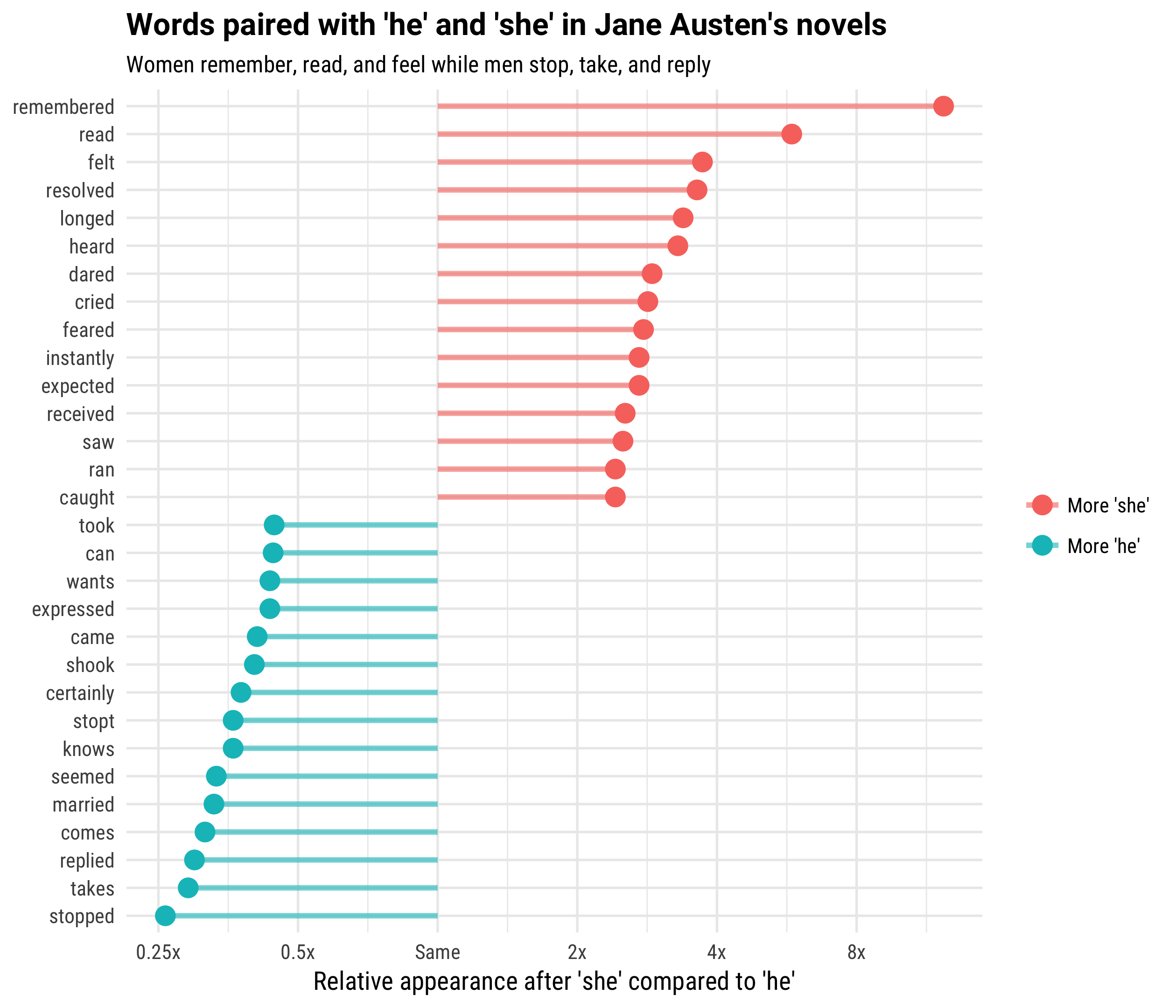

title = "Words paired with 'he' and 'she' in Jane Austen's novels",

subtitle = "Women remember, read, and feel while men stop, take, and reply") +

scale_color_discrete(name = "", labels = c("More 'she'", "More 'he'")) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = seq(-3, 3),

labels = c("0.125x", "0.25x", "0.5x",

"Same", "2x", "4x", "8x"))

These words are the ones that are the most different in how Jane Austen used them with the pronouns “he” and “she”. Women in Austen’s novels do things like remember, read, feel, resolve, long, hear, dare, and cry. Men, on the other hand, in these novels do things like stop, take, reply, come, marry, and know. Women in Austen’s world can be funny and smart and unconventional, but she plays with these ideas within a cultural context where they act out gendered roles.

George Eliot and n-grams

Let’s look at another set of novels to see some similarities and differences. Let’s take some novels of George Eliot, another English writer (a woman) who lived and wrote several decades after Jane Austen. Let’s take Middlemarch (MY FAVE), Silas Marner, and The Mill on the Floss.

library(gutenbergr)

eliot <- gutenberg_download(c(145, 550, 6688),

mirror = "http://mirrors.xmission.com/gutenberg/")We now have the texts downloaded from Project Gutenberg. We can use the same approach as above and calculate the log odds ratios for each word that comes after “he” and “she” in these novels of George Eliot.

eliot_ratios <- eliot %>%

unnest_tokens(bigram, text, token = "ngrams", n = 2) %>%

count(bigram, sort = TRUE) %>%

ungroup() %>%

separate(bigram, c("word1", "word2"), sep = " ") %>%

filter(word1 %in% pronouns) %>%

count(word1, word2, wt = n, sort = TRUE) %>%

rename(total = nn) %>%

group_by(word2) %>%

filter(sum(total) > 10) %>%

ungroup() %>%

spread(word1, total, fill = 0) %>%

mutate_if(is.numeric, funs((. + 1) / sum(. + 1))) %>%

mutate(logratio = log2(she / he)) %>%

arrange(desc(logratio))What words exhibit the largest differences in their appearance after these pronouns in George Eliot’s works?

eliot_ratios %>%

mutate(abslogratio = abs(logratio)) %>%

group_by(logratio < 0) %>%

top_n(15, abslogratio) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(word = reorder(word2, logratio)) %>%

ggplot(aes(word, logratio, color = logratio < 0)) +

geom_segment(aes(x = word, xend = word,

y = 0, yend = logratio),

size = 1.1, alpha = 0.6) +

geom_point(size = 3.5) +

coord_flip() +

labs(x = NULL,

y = "Relative appearance after 'she' compared to 'he'",

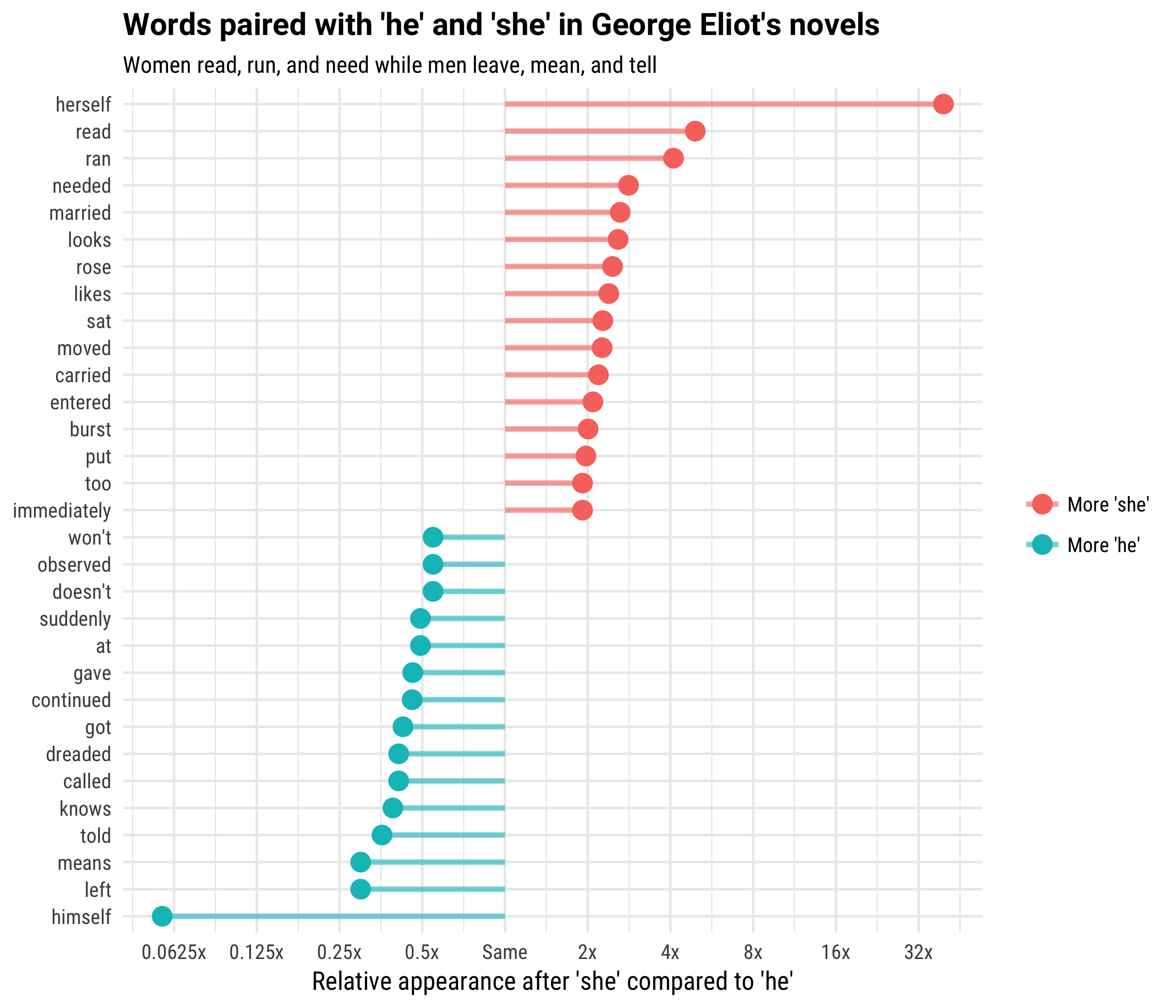

title = "Words paired with 'he' and 'she' in George Eliot's novels",

subtitle = "Women read, run, and need while men leave, mean, and tell") +

scale_color_discrete(name = "", labels = c("More 'she'", "More 'he'")) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = seq(-5, 5),

labels = c("0.03125x", "0.0625x", "0.125x", "0.25x", "0.5x",

"Same", "2x", "4x", "8x", "16x", "32x"))

We can see some difference in word use and style here, but overall there are quite similar ideas behind the verbs for women and men in Eliot’s works as Austen’s. Women read, run, need, marry, and look while men leave, mean, tell, know, and call. The verbs associated with women are more connected to emotion or feelings while the verbs associated with men are more connected to action or speaking.

Jane Eyre and n-grams

Finally, let’s look at one more novel. The original paper found that Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë had its verbs switched, in that there were lots of active, non-feelings verbs associated with feminine pronouns. That Jane Eyre!

eyre <- gutenberg_download(1260,

mirror = "http://mirrors.xmission.com/gutenberg/")

eyre_ratios <- eyre %>%

unnest_tokens(bigram, text, token = "ngrams", n = 2) %>%

count(bigram, sort = TRUE) %>%

ungroup() %>%

separate(bigram, c("word1", "word2"), sep = " ") %>%

filter(word1 %in% pronouns) %>%

count(word1, word2, wt = n, sort = TRUE) %>%

rename(total = nn) %>%

group_by(word2) %>%

filter(sum(total) > 5) %>%

ungroup() %>%

spread(word1, total, fill = 0) %>%

mutate_if(is.numeric, funs((. + 1) / sum(. + 1))) %>%

mutate(logratio = log2(she / he)) %>%

arrange(desc(logratio))What words exhibit the largest differences in Jane Eyre?

eyre_ratios %>%

mutate(abslogratio = abs(logratio)) %>%

group_by(logratio < 0) %>%

top_n(15, abslogratio) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(word = reorder(word2, logratio)) %>%

ggplot(aes(word, logratio, color = logratio < 0)) +

geom_segment(aes(x = word, xend = word,

y = 0, yend = logratio),

size = 1.1, alpha = 0.6) +

geom_point(size = 3.5) +

coord_flip() +

labs(x = NULL,

y = "Relative appearance after 'she' compared to 'he'",

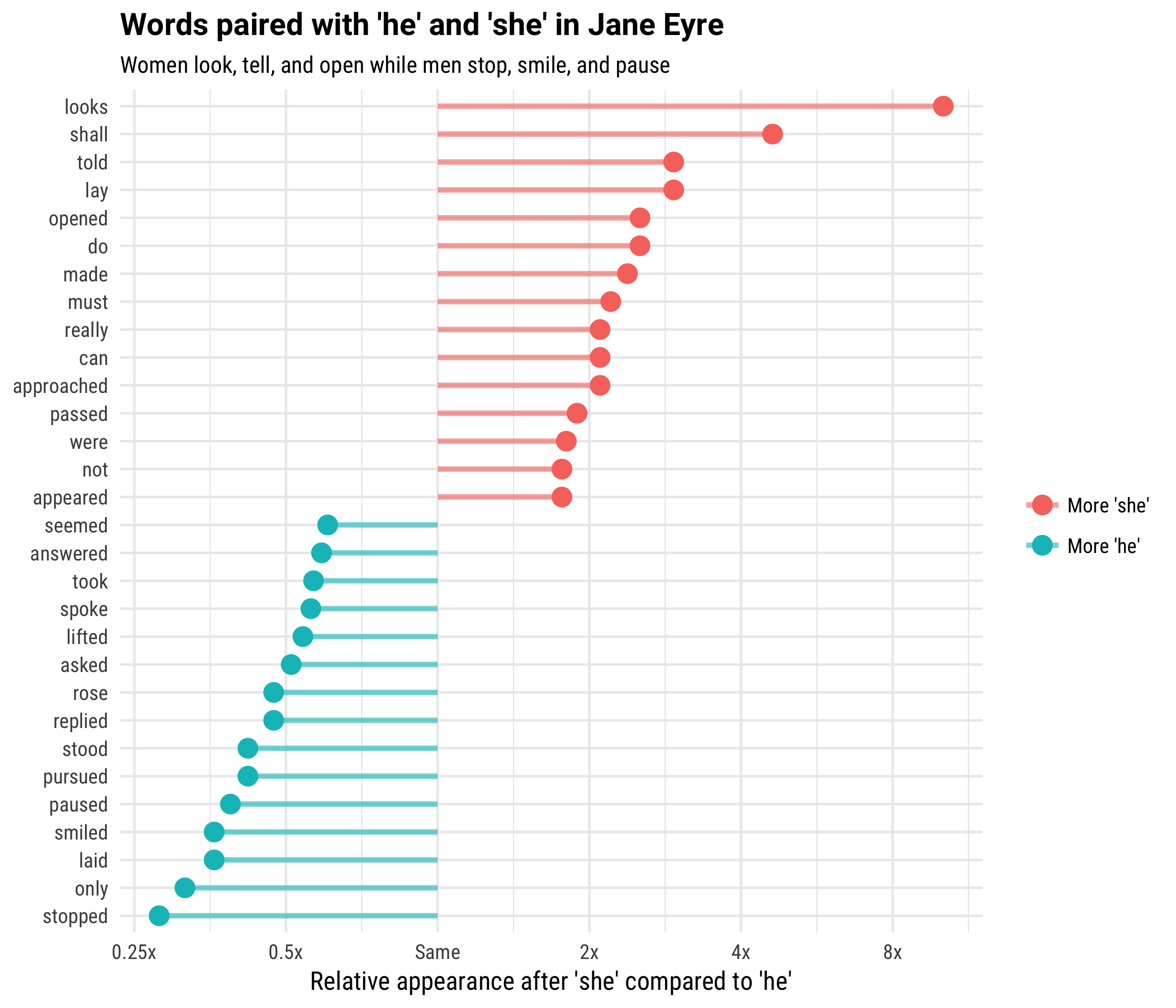

title = "Words paired with 'he' and 'she' in Jane Eyre",

subtitle = "Women look, tell, and open while men stop, smile, and pause") +

scale_color_discrete(name = "", labels = c("More 'she'", "More 'he'")) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = seq(-3, 3),

labels = c("0.125x", "0.25x", "0.5x",

"Same", "2x", "4x", "8x"))

Indeed, the words that are more likely to appear after “she” are not particularly feelings-oriented; women in this novel do things like look, tell, open, and do. Men in Jane Eyre do things like stop, smile, pause, pursue, and stand.

The End

It is so interesting to me how these various authors understand and portray their characters’ roles and gender, and how we can see that through analyzing word choices. The R Markdown file used to make this blog post is available here. I am very happy to hear about that or other feedback and questions!